The killer application for every new technology is a billion-dollar application that already exists.

That sounds kind of boring, right? Shouldn’t killer apps be a bit more exciting? And as we think about 5G wireless, shouldn’t the massive investment in 5G create something revolutionary? The metaverse, perhaps? Robotic surgery? Industry 4.0? Or maybe, millions of private 5G networks, running on AWS?

Surely some of this will happen, but if history is our guide, it will take time. If we think of the past, we know that the automobile replaced the horse buggy. The PC replaced the typewriter. Uber replaced taxis. Airbnb offered an alternative to hotels. And when Steve Jobs launched the first iPhone, he introduced it as a computer in your pocket.

In the late 1990s, 3G was expected to herald the golden age of the mobile Internet. European operators paid more than $100B to buy spectrum. Ericsson, Nokia, and Motorola, the three biggest phone manufacturers at that time, created the Wireless Application Protocol (WAP) and launched devices. The fine folks at Qualcomm countered with BREW. The excitement was palpable. On a personal note, in April 2000, I almost dropped out of business school to start a marketplace for local services — running on WAP! I am glad I didn’t. WAP was unusable and the iPhone was still eight years away.

Yet, despite the failures of WAP, BREW, and all the early wireless internet devices, mobile carriers invested in building 3G networks. Why? What was the killer app that provided a business case for 3G investment?

Believe it or not, the killer app for 3G cellular turned out to be replacing landline telephony. 3G networks increased the voice capacity of mobile operators by 10X, if not more. Not only did 3G networks offer higher spectral efficiency (3x higher bits per Hz) than 2G, but 3G took advantage of wider channels. While a 2G/GSM base station operated in a few 200 kHz channels, a 3G/UMTS base station could operate in 5 MHz channels.

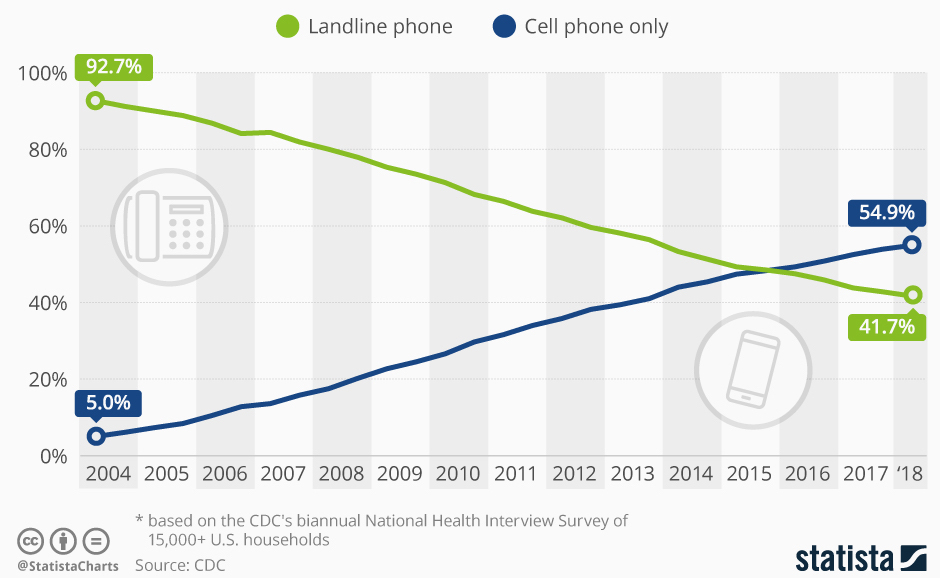

With 3G networks built, mobile operators were awash in voice capacity, and the price of voice calls plummeted. Flat rate plans replaced per-minute plans. Want 1000-minutes a month with no long-distance charges? By 2004, you could do so on a mobile phone, anytime, anywhere at a very affordable price. Soon mobile phones started displacing landlines. The first 3G networks were launched in the fourth quarter of 2001. By 2010, several US carriers were offering unlimited voice plans for about $70, and 30% of US households had cancelled their landline phones. Mobile ARPU increased, at the expense of landline revenue. It would be fair to say that the shift of landline voice revenue to mobile voice funded the 3G build-out.

As we enter the 5G era, I would posit that the killer app for 5G will be home broadband. I would not be surprised if, by 2030, 30% of households access broadband over 5G.

5G-based home broadband will not change our lives, but it will surely pay for the buildout of 5G networks that other applications can ride on. In the United States alone, home broadband is a $90B/year market with opportunities to upsell everything from streaming services to home security systems. And this opportunity to increase average revenue per account (ARPA) has not been missed by mobile operators that are making massive investments in 5G.

For example, Verizon and T-Mobile have embraced home broadband as one of their biggest growth opportunities. Verizon, in its Q3 2021 earnings call and subsequent investor conferences, has laid out its vision of becoming a national broadband provider, setting a target of offering service to 50M households (or 38% of all US households) by 2025. And it is sufficiently confident of its plans that it recently started reporting the number of wireless home broadband subscribers on a quarterly basis. T-Mobile has similarly laid out a goal of acquiring 7–8 million home broadband subscribers by 2026.

There is one big difference between displacing landline voice and displacing wired broadband, though. While there is a limit on the voice minutes that a subscriber can consume (on average, less than 800 minutes per month in the US), the demand for data does not have seem to have such a limit, at least not yet. According to OpenVault, home broadband users on average consumed more than 430 GB in Q2’21, with 10% of subscribers consuming more than 1 TB.

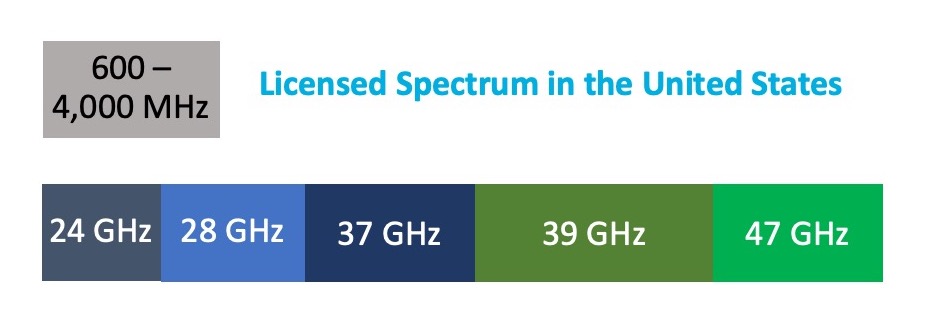

This means that to win in the home broadband market, 5G operators will have to bring all their spectrum assets to bear. Low- and mid-band spectrum will be critical to get started in this market, but it will not be enough to provide the network capacity for double digit market share. Long-term success in this market will require cost-effectively harnessing abundant high-band, millimeter wave spectrum.

A new year will soon be upon us. And though I would love to watch immersive VR on my 5G-connected flying taxi from Silicon Valley to San Francisco, I will be content with replacing my cable broadband with a nice, solid, 5G-based home broadband connection. With that fond hope, I raise a glass to 2022!

Recent Comments